July 6, 2015

The Declaration Of Independence, The Constitution, And The Gout

By Michael D. Shaw

As we celebrate the 239th anniversary of the approval of the Declaration of Independence by the Continental Congress, let’s take a look at a health problem bedeviling certain signers of the famous document, and its effect on our history. A common affliction—affecting at least seven of the 56 signers—was gout. Sufferers included Benjamin Franklin (PA); John Hancock (MA); Benjamin Harrison (VA); Thomas Jefferson (VA); George Ross (PA); Edward Rutledge (SC); and George Walton (GA).

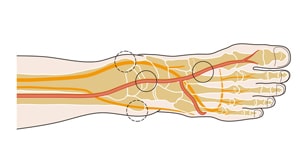

Gout is a particularly painful form of arthritis, resulting from the deposition, in and around the joints, of uric acid salts. While any peripheral joint can be affected, the most usual site is the joint at the base of the big toe. Gout attacks generally subside within a week or two, and sufferers often claim that they can come on for no apparent reason. Still, documented precipitating factors include emotional upset, excessive alcohol consumption, poor diet, obesity, diuresis, surgery, trauma, and the administration of certain medications. Typically, the disease first strikes in middle age.

Since most of the signers were upper crust, and overindulgence in meats, seafood, and alcohol was only possible in those days among people of means, the incidence of gout in this cohort is hardly surprising.

John Hancock’s life, especially, would be affected by the disease. Considering that he only lived to be 56, he was well into middle age at the time of the Declaration, and no doubt had several attacks during his term as president of the Congress (1775-1777). But more significant attacks were yet to come. Indeed, some historians insist that ratification of the Constitution turned on John Hancock’s big toe.

How so? Most scholars agree that there would have been no Constitution without the participation of George Washington, who truly wished to stay out of public life at that point. As it happens, several signers of the Declaration, including Hancock and Richard Henry Lee, were at least initially opposed to ratification. Moreover, the prevailing public sentiment was not in favor of transferring sovereignty to a central government. Painful memories of the Revolution and life under an autocratic England were only a few years old.

The stratagem to assure Washington’s participation was a letter sent to him—on October 23, 1786—by one of his former generals, Henry Knox. Gary North calls it “[T]he most influential direct-response sales letter in the history of the United States.” Essentially, Knox was able to spin a gross distortion of Shays’ Rebellion (August 1786–February 1787) into the spurious notion that the anti-Federalists were “Shaysites,” and those dedicated to law and order were the Federalists. Thus, “Your country needs you again, George.”

Shays’ Rebellion was an uprising in western Massachusetts in opposition to high taxes and stringent economic conditions. Armed bands forced the closing of several courts to prevent execution of foreclosures and debt processes. There was widespread public support.

Now, about that big toe: Hancock was the first (October 25, 1780 – January 29, 1785) and third (May 30, 1787 – October 8, 1793) governor of Massachusetts, and was sympathetic to the plight of the debtors, whose ranks included many Revolutionary War veterans. Alas, he was unable to run for governor in 1785, being struck with a terrible gout attack, and his political and social rival James Bowdoin took office.

Bowdoin and his cronies were large creditors, and, unlike Hancock, made aggressive moves to collect—which sparked Shays’ Rebellion. Absent the gout, Hancock, by far the most popular politician in Massachusetts, would have surely won the election, and there would have been no rebellion. Upon his re-election, Hancock pardoned all the rebels.

Gout would continue to plague the governor. When he arrived at the Constitutional Convention in Boston on January 30, 1788, his feet were heavily bandaged, and he was carried to his chair. By virtue of the addition of the Bill of Rights, Hancock voted for ratification, and persuaded longtime opponent of Federalism Samuel Adams to do the same. Massachusetts would ratify on February 6, 1788, becoming the sixth state to do so. Ratification carried by 187–168, and there is little doubt that without Hancock’s influence, it would have failed.

Historian North goes further, and contends that Shays’ Rebellion provided the opportunity for our Framers to pull a fast one, against the wishes of the majority, creating a strong central government.

Ironically, gout is more commonplace today than in the 18th century, as if to serve as a reminder of its importance in our nation’s history.