April 27, 2009

Colonoscopes, Reprocessing, Connectors, And Infection

By Michael D. Shaw

Just in time for Christmas—on December 22, 2008—the US Department of Veterans Affairs issued a Patient Safety Alert entitled “Improper set-up and reprocessing of flexible endoscope tubing and accessories.” The major finding was that certain tubing modified with an incorrect connector was used to attach an Olympus flexible endoscope to its irrigation source.

This resulted in a backflow of body fluids into irrigation source tubing—where backflow should not occur—during an endoscopic procedure (i.e. a colonoscopy). In other words, supposedly clean irrigation solutions were being contaminated with the patient’s body fluids, promoting cross-contamination.

It was also discovered, and reported in the same Patient Safety Alert, that a related component of the endoscopes was being reprocessed (sterilized or disinfected) only at the end of the day rather than after each patient use, as is required by the manufacturer’s reprocessing instructions.

Per the Alert, all VA facilities were to investigate their procedures and report back. Media sources indicated that the problems described occurred at the VA hospital in Murfreesboro, TN.

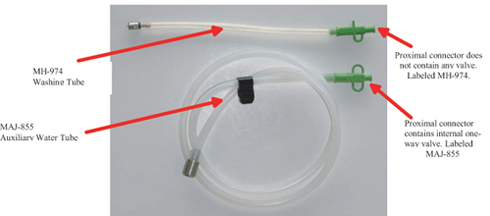

At the heart of the matter are two particular tubes, used in both the actual patient exams and in reprocessing. The tubes are different in appearance: Tube MH-974 is about 10 inches in length (254 mm), while Tube MAJ-855 is around 4 feet (1.2 m) long. Each tube is provided with its own specific connector. MH-974’s connector does not contain a valve, while MAJ-855’s connector contains an internal one-way valve.

The connectors are very similar in appearance, except for one “wing” in MH-974’s, and two wings in MAJ-855’s. The connectors are labeled to indicate which tube they belong to.

As Olympus describes it in their “Important Safety Notice” of January 26, 2009: The one-way valve in the proximal connector of the MAJ-855 prevents backflow of fluids from the auxiliary water channel of endoscope into the flushing pump tubing. The one-way valve also prevents water from flowing out of the proximal connector of the MAJ-855 when disconnecting the syringe (used in manual reprocessing) or the flushing pump tubing from the MAJ-855.

On February 13, 2009, the Murfreesboro facility sent letters to nearly 6,400 veterans warning that improperly assembled colonoscopy equipment may have exposed them to Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, and HIV. This improper assembly could have occurred anytime between April 23, 2003 and December 1, 2008.

From March 8-14, 2009, the VA initiated a “step-up” program whereby all facilities were to check if they have contamination problems, and to arrange new training programs. Based on this new inspection protocol, the Miami VA Medical Center discovered that it, too, has endoscope reprocessing issues. On March 23, Miami VAMC sent letters to about 3,260 veterans, warning that if they had colonoscopies at the facility, improperly sanitized equipment might have exposed them to Hepatitis B, Hepatitis C, or HIV.

By April 17, one case of HIV, five of Hepatitis B, and 11 of Hepatitis C were reported for Murfreesboro. Miami results so far indicate one case of HIV, none of Hep B, and seven of Hep C.

The VA said that there was no way to prove that the patients contracted the illnesses because of treatment at their facilities. However, I would point out that genome analysis (in effect, forensics on the pathogen) and a recent history on the affected individuals would remove most of the doubt. If DNA analysis (RNA in the case of Hep C) showed the same genome, and the patient showed no risk factor other than the colonoscopy, one could be reasonably sure of the source of the infection.

What about the notion that “this improper assembly could have occurred anytime between April 23, 2003 and December 1, 2008”? That’s a time span of more than five years. What could have gone wrong?

It is noted that the Olympus endoscope-reprocessing manual recommends the use of the MAJ-855 auxiliary water tube to manually process a portion of the endoscope called the auxiliary water channel. But, medical facilities have at their disposal expensive units called automated endoscope reprocessors (AERs). Why do something by hand if you have a machine?

Sources tell us that one AER manufacturer informed its customers—via a technical bulletin—that MAJ-855 could be reprocessed using its AER, as long as an adapter or connector without a restrictive one-way valve (for example, the MH-974’s similar-looking adapter, which has no internal valve) was used with it.

Fair enough, but this is an accident waiting to happen, is it not? For patient use, MAJ-855 must be provided with its proper connector, containing that one-way valve. Otherwise, dangerous backflow is allowed. And, since these two connectors have a similar appearance, one can virtually guarantee that on occasion, the proper connector will not be put back on tube MAJ-855.

Based on this scenario, it is quite unlikely that the problems will be limited to only VA facilities.

Before blame is assessed, and there is surely more than enough to go around, we might ask where the regulatory agencies and non-governmental organizations were, that supposedly are watching over us in these matters.