June 29, 2009

The Sense Of Light Touch Really Is Activated By Merkel Cells

By Michael D. Shaw

“Light touch” refers to the body’s ability to respond to the slightest touch. When you feel a subtle texture, a gentle breeze on the back of your neck, or a tiny insect crawling on your arm, this is the sense of light touch. Certain neurological procedures will use a safety pin to test the pain response, and wispy cotton fibers to test the light touch function in patients.

But, what are the receptors for this subtle sense?

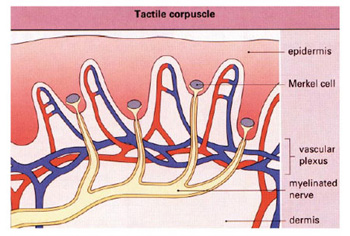

Way back in 1875, German anatomist Friedrich Sigmund Merkel referred to certain cells in the skin—at the bottom of the sweat duct ridges—as Tastzellen or “touch cells,” although they were named in honor of Merkel by another German, physician Robert Bonnet, in 1878. These cells appear in all vertebrates.

The “touch cell” concept was assumed to be true by many for years, but had never been proven—until now.

Drs. Ellen Lumpkin, Huda Zoghbi and team (mostly of Baylor College of Medicine) produced a group of mice that lacked the gene Atoh1 in their body skin and footpads. Atoh1 is a transcription factor vital for the creation of Merkel cells.

Laboratory tests indicated that the skin/nerve preparations from the subject mice showed a complete loss of the characteristic neurophysiologic responses normally mediated by Merkel cell-neurite complexes. The authors noted that other touch-sensitive neurons were still working, but the receptors for high spatial resolution i.e. light touch were missing.

Co-author Stephen Maricich calls this the “first direct evidence” of the link between the Merkel cells and light touch. This research appears in the 19 June 2009 issue of Science, and is entitled “Merkel Cells Are Essential for Light-Touch Responses.”

About ten years ago, Dr. Zoghbi and other Baylor scientists identified Atoh1, and showed its involvement in hearing and propioception (the perception by an animal of stimuli relating to its own position, posture, equilibrium, or internal condition).

Dr. Lumpkin commented that Merkel cells and hair cells (sensory cells of the ear) “allow you to manipulate objects with high spatial resolution and discrimination of sound. That’s what I think is beautiful about Atoh1, the Merkel cell, and the hair cell.”

She elaborated: “These cells are the first way our body interacts with the outside world. Both hair cells and Merkel cells tell us what and when at the finest level we humans relate to our environment.”

Dr. Zogbhi added: “This is another important component of the Atoh1 network that helps people realize where they are in space. While the specific activity of Merkel cells permit light touch and the ‘what and when’ of activity, Atoh1-dependent neurons are processing that information.”

But Dr. Lumpkin wants to probe deeper. “We don’t know how any mammalian touch receptor works. What genes allow them to function as light or painful touch receptors? This project gives us the experimental handle with which to start to dissect the genetic basis of touch.”

Lumpkin’s research interests involve how somatosensory neurons detect and respond to mechanical stimuli. She notes that their importance to human health is demonstrated all too well in diseases which can cause the death of these neurons, such as diabetes and AIDS.

One other side of Merkel cells is a somewhat rare but highly aggressive form of cancer called Merkel cell carcinoma. Recently, a virus has been implicated in about 80 percent of the cases.

As to the Tastzellen, it looks like Dr. Merkel was right, and ahead of his time by 134 years.