July 9, 2007

Can Buckyballs Improve Your Health?

By Michael D. Shaw

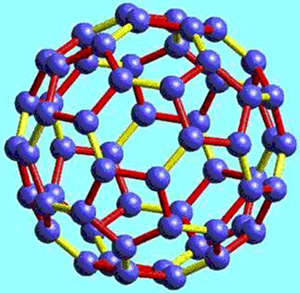

What, you might ask, is a “buckyball”? Named after iconic architect R. Buckminster Fuller, a buckyball is a hollow carbon molecule in the form of a closed cage, akin to Fuller’s famous geodesic dome. The most elegant of these is the highly symmetrical C60 version, consisting of 12 pentagonal and 20 hexagonal faces, resembling a soccer ball.

Discovered only in 1985, these molecules—generically termed fullerenes (which also include a cylindrical format)—represent a third form (allotrope) of carbon. Graphite and diamond had been known since ancient times, but fullerenes had eluded detection, despite available technology.

Soon after their discovery, materials scientists began touting their amazing properties, such as incredible tensile strength, and current-carrying capacity. There are also biological applications.

In 1997, Washington University (St. Louis) researcher Laura Dugan found that buckyballs modified with carboxyl side chains (one carbon, two oxygens and one hydrogen) to make them water soluble, protected nerve cells from free radical damage. The buckyballs also delayed symptoms and death in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS—Lou Gehrig’s disease).

At the time, Dugan noted:

“These molecules protect nerve cells from a much wider range of harmful events than any other compounds we’ve tested. Our working hypothesis is that the buckyballs act as generalized radical scavengers that prevent oxidative damage to cell membranes. They also may interrupt the cell-suicide chain of commands.”

More recent work suggests that there could also be immune system implications.

A group led by Chris Kepley of Richmond’s Virginia Commonwealth University was able to interrupt the allergy/immune response by inhibiting a basic process in the cell that leads to the release of an allergic mediator. They found that buckyballs can prevent cultured human mast cells from releasing histamine.

Mast cells mediate inflammatory responses such as hypersensitivity and allergic reactions. They are scattered throughout the connective tissues of the body.

Kepley reported similar effects in vivo with mice injected with buckyballs. Compared to the control group, the injected mice were far less susceptible to life-threatening anaphylactic allergic responses.

While there is certainly more to allergic reactions than simply histamine, many in the field are excited with the notion of using nanoparticles for therapeutic purposes.

As Kepley said,

“This discovery is exciting because it points to the possibility that these novel materials can one day lead to new therapies. The immune system both protects us and causes harm, so we are always interested in finding new pathways to help manage the harmful effects.

The study was done as a collaboration with the nanoWorks division of Luna Innovations, a Roanoke-based R & D and manufacturing company. Division president and study co-author Robert Lenk is enthusiastic:

“Our experiments could be the beginning of an entirely new field of medicine we are calling nanoImmunology. We are excited about the potential possibilities in immunotherapeutics and other medical disorders that may be possible with these compounds.”

For those concerned about the use of harsh pharmaceuticals, few substances could be more benign than carbon, the basic building block of all life.