January 5, 2009

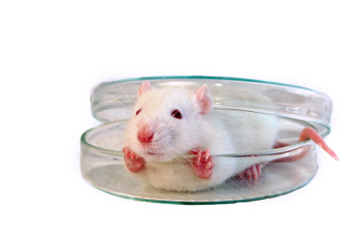

Curing Mice But Not Humans

By Michael D. Shaw

The March 22, 2004 issue of Fortune magazine featured an article entitled “Why We’re Losing The War On Cancer.” One big point the article made was that rodent models are not predictive of therapeutic effects in humans. Indeed, the article was chock full of quotes like this one from Homer Pearce, a research fellow at Eli Lilly: “If you look at the millions and millions and millions of mice that have been cured, and you compare that to the relative success, or lack thereof, that we’ve achieved in the treatment of metastatic disease clinically, you realize that there just has to be something wrong with those models.”

Others quoted confirmed that the mouse model is favored because it is easy to use, and it is still highly regarded by the FDA, despite its lack of success or even applicability to the nature of human cancers. Various studies indicate that the failure rate of animal-qualified anti-cancer drugs is 95%. Moreover, the case of the Novartis drug Gleevec showed that a drug which was nearly abandoned because of liver toxicity in dogs, ended up being extremely useful in humans.

Of course, cancer is by no means the only place that questionable rodent studies have set policy. Last August, the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act of 2008 was signed into law by President Bush. Section 108 of this bill provides for the prohibition on sale of certain products containing phthalates—chemicals that have been used for decades to soften plastics.

Specifically, as of November 12, 2008, it is unlawful for any person to manufacture for sale, offer for sale, distribute in commerce, or import into the United States any children’s toy or child care article that contains concentrations of more than 0.1 percent of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), or benzyl butyl phthalate (BBP).

Additionally, similar regulatory provisions apply to any children’s toy that can be placed in a child’s mouth or child care article that contains concentrations of more than 0.1 percent of diisononyl phthalate (DINP), diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP), or di-n-octyl phthalate (DnOP).

Forget for a moment that the short time frame on the bill is wreaking havoc in the plastics and retailing industries, and that even this time frame is being challenged in a lawsuit that wants to make it retroactive to existing inventory. This measure sounds very enlightened and protective, until you discover that virtually all the science involved here is based on rodent models with no relevance to humans, and that the enforcing agency (Consumer Product Safety Commission) has its own science that disputes the need for such restrictions.

Fortunately, an immunologist is speaking out regarding over-reliance on the mouse model. Stanford professor Mark Davis’ essay entitled “A Prescription for Human Immunology” appears in the December 19, 2008 issue of Immunity.

He points out that humans and mice are separated by 65 million years from our common ancestor, and that while humans reach sexual maturity in about 20 years, mice get there in three months. As such, during the nearly 100 years that lab mice have been used, this amounts to the mouse equivalent of 8,000 human years, during which they have been inbred and kept relatively disease-free. They would never survive in the wild, says Davis.

He reminds us that in the past 8,000 years of human history, and our gathering in cities…

“We’ve been selected by urbanization, with plagues such as the bubonic plague and smallpox that routinely killed huge numbers of people, and modern scourges like HIV and malaria that still infect and kill millions each year. Most humans are infected with six different herpes viruses, and who knows what else. And while we’re suffering away, getting colds and flu, the mice are living in the lap of luxury in miniature condominiums, with special filters on the cage tops to keep bad things out.”

One wonders how well these mice can accurately reflect the human condition.

Davis suggest a bold new approach to the study of human immunology, inspired by the “big science” methods of the Human Genome Project:

Millions of blood and tissue samples are currently available, based on the huge health care systems worldwide. Government funding could focus on studies of “normal” volunteers whose results could be assayed in parallel to the hospital samples of the ill. The millions of people vaccinated could become part of a study of normal immune systems activated in a generally safe manner.

In essence he is proposing a “systems” approach to immunology in humans, comparing sick and healthy individuals. Ironically, when this has been done via epidemiological studies of humans, to examine the effect of certain chemicals, the invariable result is that humans do not react to them as mice did!

Let us no longer be trapped in the mouse model.