June 13, 2005

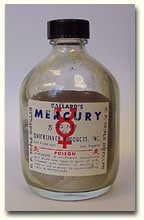

Mercury Rising

By Michael D. Shaw

In previous articles, we have tried to inject some science and sanity into the hysteria generated over certain toxic substances in our environment. While most popular coverage of this topic wildly overstates the risks, there are still individual differences—both in a given person’s susceptibility, and in the true danger posed by a particular toxic agent. Environmental tobacco smoke and toxic mold, for example, generally affect only highly allergic people, and radon is hazardous only at concentrations orders of magnitude higher than what is encountered in residences. Moreover, in both of these cases, actual hard scientific data on human exposure is sorely lacking.

Then, there’s mercury. With this chemical, there is no shortage of human exposure data or real life experience. Although use of and exposure to mercury dates back to ancient times, the first popular recognition of its health effects spawned the expression, “Mad as a hatter.” When mercury salts, in prodigious quantities, were used in the felting process for hat manufacturing, many of the workers developed strange twitches, shakes, and personality changes, making them appear crazy to outside observers. Since mercury poisoning is cumulative, the nervous system effects were the initial symptoms, followed by a premature demise, in many cases.

How about a little known historical tidbit? Abraham Lincoln, described by friend and foe alike as even tempered during his presidency, was subject to fits of uncontrollable rage just a few years earlier. This character improvement occurred right after he stopped taking his mercury-laden little blue pills, prescribed to control his melancholia, in 1861, observing that they made him “cross.”

In modern times, the best known example of mercury poisoning involved the Japanese chemical firm Chisso Corporation, that dumped untold thousands of tons of various mercury compounds into Minamata Bay, from the 1930’s until 1968. A number of hapless consumers of fish from the bay either died summarily, or suffered serious symptoms. Many pregnant women who ate this fish gave birth to babies that had deformed limbs, severe retardation, or both. The sorry situation became notorious as a result of W. Eugene Smith’s widely publicized 1972 photo of a mother bathing her afflicted daughter, even though reports of victims began surfacing 19 years earlier.

Two separate outbreaks of mercury poisoning occurred in Iraq (in 1960 and the early 1970’s), based on the consumption of seed grain treated with a mercury-containing fungicide, that was instead ground for flour. Unlike the exposures in Japan, this poisoning was a short-term, higher exposure event. Still, the health effects were about the same, especially to those exposed in utero.

These cases were horrific, no doubt about it, but we must be careful about the lessons we learn here. Our guiding light, as always in these matters, is the basic maxim of toxicology: The dose makes the poison. In these cases, the exposures to mercury were huge, exceeding anything we might be likely to encounter. They were also the results of misdeeds and misadventures, and fortunately are rare anecdotal events. Regulations were written as a result of disasters such as these.

Should we avoid seafood, as some have suggested, since it might be contaminated with mercury? In an ideal world, simple choices would exist between perfectly healthy and unhealthy alternatives. Most fish is a good protein source, low in harmful fats. What about all the problems with meat? Don’t the higher fat content and presence of contaminants create concerns, as well?

A prudent course would be for pregnant women, since their offspring appear to be at the greatest risk, to not overindulge in seafood. However, even for this cohort, eliminating seafood completely is definitely overkill, unless you believe that all the world’s fishing grounds are as contaminated as Minamata Bay was 50 years ago.

What about amalgam dental fillings? Getting them removed for cosmetic appeal is one thing, but the data is simply not there to justify removing them for health reasons. Certainly, for any future fillings, and if you can afford the price difference, go for the composites (even if they probably don’t wear as well as the amalgam).

Mercury is but one of thousands of toxic substances in our environment, and our approach to these potential dangers should be directed by good science and common sense. Let us studiously avoid the sensational and the shrill.