December 25, 2006

The Story Behind The Bacterial Outbreak That Killed Two Preemies In Los Angeles

By Michael D. Shaw

If you’re familiar with this tragic case that occurred a few weeks ago in an LA neonatal unit, you may have also heard that the infection was traced back to an “improperly sterilized laryngoscope,” according to the Associated Press story. And, in the words of Dr. Laurene Mascola, director of Los Angeles County’s acute communicable disease control unit, “It’s a done deal. We have the smoking gun.”

Sorry, Dr. Mascola, but what we have here is anything BUT a done deal.

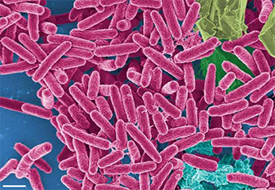

The bug that killed the two babies was Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium infamous for its ability to thrive in numerous environments, its tendency to cause disease in immunocompromised individuals, and its resistance to antibiotics. P. aeruginosa produces toxic proteins that can destroy tissue and interfere with the immune system, and is said to be responsible for 10 percent of the 2 million hospital-acquired infections that happen each year. Of the 2 million infections, nearly 100,000 are fatal.

As to the “improperly sterilized laryngoscope,” possibly, the hospital officials quoted in the AP story were not being precise in their terminology.

“Sterilization” is any process whereby all forms of microbial life (bacteria, spores, fungi, and viruses) are completely destroyed.

In practice, though, laryngoscopes are usually not sterilized, since AORN (Association of Perioperative Registered Nurses) guidelines recommend high-level disinfection of the laryngoscope blades, and, incredibly, recommend low-level disinfection for the laryngoscope handle.

“High-level disinfection” is expected to destroy all microorganisms, with the exception of high numbers of bacterial spores. “Low-level disinfection” can kill most bacteria, some viruses, but it cannot be relied on to kill resistant microorganisms such as tubercle bacilli or bacterial spores.

Since laryngoscopes are considered to be “semicritical” devices (in accordance with the so-called Spaulding classification scheme—as the device touches mucous membranes), high-level disinfection is indicated. Note that low-level disinfection is recommended for “noncritical” items—the items that would only touch intact skin.

However, as any undergraduate microbiology student will tell you, once a surface that started off at a higher level of disinfection is touched by a surface that is at a lower level—such as a laryngoscope blade touching a laryngoscope handle—the higher level surface has been compromised. Indeed, this would be a fundamental violation of aseptic technique.

Thus, you might well ask, why in the world would the guidelines provide for such sloppy technique? In two words: Cost savings.

Laryngoscopes typically come as one handle with several blades. While there would be sufficient inventory to allow for the more time-consuming process of high-level disinfection for the blades, there might not be enough handles in stock to allow this. The result is a compromised instrument, and this, alone, could explain the LA tragedy.

Widely published infection control guru Dr. Lawrence F. Muscarella has objected to this practice, and has cited numerous literature references proving that contamination can occur. Check out his comprehensive website.

Given that Pseudomonas aeruginosa has been identified as the culprit, it is important to consider one other possible scenario.

Although this bug can live in many places, it does exceptionally well in moist environments, is found in tap water, and was said to be observed in the sinks at the very hospital involved in the deaths. Indeed, P. aeruginosa is often observed growing in distilled water.

“It would be difficult to identify another ‘recommended’ medical practice that poses as significant a risk of nosocomial [hospital-acquired] infection from, for example, waterborne bacteria (including Pseudomonas aeruginosa) as the introduction of wet endoscopes into patients’ organs and cavities.”

“No data or studies have been published that support the claim that ‘sterile’ rinse water can be produced by filtering a hospital’s tap water through a water filtration assembly that includes a 0.2 micron bacterial filter.” [This comment is in reference to a particular well-known and ubiquitous reprocessing device.]

Muscarella maintains that the risk of transmission of bacteria during scope procedures can be virtually eliminated by drying the endoscope after completion of every reprocessing cycle. While this practice is not supported by AORN, it is recommended by the Society of Gastroenterology Nurses and Associates (SGNA) and the American College of Chest Physicians.

Finally, Muscarella believes that AORN’s guidelines have lowered the levels of diligence, vigilance, compliance, and concern regarding the potential for disease transmission associated with improper reprocessing of endoscopes (including laryngoscopes). The guidelines seem to be disproportionately influenced by cost factors and the peculiarities of certain manufacturers’ reprocessing equipment, rather than patient safety.

It’s high time that patients, their loved ones, and the physicians who treat them demand better infection control procedures in hospitals, and that includes tightening up guidelines such as those mentioned in this article. Only then, will we have a “done deal.”