April 23, 2007

Take Out The Salt, To Fight The Drought

By Michael D. Shaw

Global warming or not, drought has always been with us. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) has estimated that drought costs the United States $6 to $8 billion annually, while floods and hurricanes average $2.4 billion and $1.2 to $4.8 billion, respectively.

Whether your preferences run to Samuel Taylor Coleridge–

Water, water, everywhere,

And all the boards did shrink;

Water, water, everywhere,

Nor any drop to drink.

or Benjamin Franklin–

When the well is dry, we learn the worth of water

no one can deny the seriousness of this issue.

Water shortages are painfully ironic on a planet whose surface is 71 percent water, but the double irony is that 97 percent of this is saltwater. Moreover, at least 68 percent of the freshwater is locked up in glaciers and icecaps, mainly in Greenland and Antarctica. Another 30 percent of the freshwater is groundwater—located in aquifers below the earth’s surface. In fact, there is a hundred times more water in the ground than is in all the world’s rivers and lakes, even if it is not quite as easy to obtain.

But, that’s the point: It is time to look beyond the simple solutions, and embrace an idea that is hardly new—desalination. Aristotle wrote about an evaporation method used by Greek sailors in the 4th century BC, and an Arab writer of the 8th century detailed a distillation process.

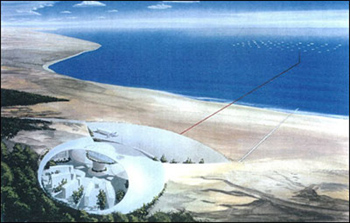

At present, 11,000 facilities operate in 120 countries around the world, with a global capacity of 4 billion gallons daily. While most of this capacity is in the Middle East, there are about 1,200 plants in the US, with a new plant in Tampa processing 25 million gallons per day.

Distillation is still the most widely used process for desalination, although the more modern technique of reverse osmosis (RO), whereby water under pressure is forced through semi-permeable membranes, is definitely coming on strong.

When one considers alternatives to traditional surface sources of freshwater, such as importation, dams, or wells, RO looks better and better. In 1992, the cost to desalinate an acre-foot of water was about $2,000. Today, that cost is less than $800 per acre-foot, while the cost of importing water has risen to about $500. Experts anticipate that these costs will soon intersect. [An acre-foot is the volume of water necessary to cover one acre of surface area to a depth of one foot. This is 43,560 cubic feet (325,851 US gallons; 1233.5 cubic meters).]

Conservation is laudable and necessary, but increasing demand for freshwater leaves little doubt that desalination will have to be expanded. Bear in mind that in the wake of urban development, aquifers are being contaminated by overtaxed sewage treatment plants and failing septic systems; pesticide and fertilizer runoff; not to mention polluted runoff from roads and parking lots.

Yet, as the Natural Resources Defense Council reports, aquifer pollution isn’t the only consequence of urban growth:

“As the impervious surfaces that characterize sprawling development—roads, parking lots, driveways, and roofs—replace meadows and forests, rain no longer can seep into the land to replenish our groundwater supply. Instead, it is swept away by gutters and sewer systems.”

In Marin County, California, a recent engineering report concludes that desalination is no longer a fantasy but a necessity. According to the report, a desalination plant would make the area “drought-proof.”

The GAO (US Government Accountability Office) has stated that even under normal water conditions, 36 states anticipate water shortages in the next ten years. Do any of us even want to consider the ramifications of government mandated water rationing?

Opponents of desal plant expansion include the typical NIMBY (not in my backyard) types, along with those who complain of the amount of energy necessary, the expense, and the possible effects of desal waste products. No doubt, problems will have to be worked out, and on the expense side we already noted the huge and often ignored cost of drought.

Besides the very air we breathe, there is nothing more basic to the environment, and nothing more essentially “Green” than pure freshwater for a very thirsty world.