February 7, 2011

BPA And The Precautionary Principle: Turning Tables On The Fear Entrepreneurs

By Michael D. Shaw

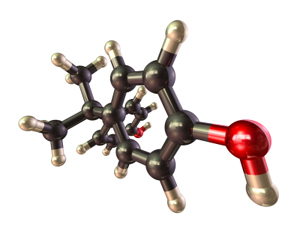

Bisphenol A (BPA) is an industrial chemical used primarily to make polycarbonate plastic and epoxy resins. A major application of epoxy resins is as a protective coating in metal cans to maintain the quality of canned foods and beverages. Specifically, the coating is essential to prevent corrosion of the can and contamination of food and beverages with dissolved metals and bacteria.

As such, BPA is in widespread use, and owing to improvements in analytical technology, as well as environmental concerns, it is one of the most heavily studied chemicals of all time. Indeed, there are more than 6000 scientific papers devoted to this compound.

Since BPA does appear in so many consumer products, it has become a favorite target—perhaps THE favorite target—of fear entrepreneurial and “environmental” fund-raising groups. Even though there is not a scintilla of evidence showing harm to humans at any rational level of exposure to this chemical, BPA has been a successful fund-raising scapegoat for five main reasons:

- Minute (but harmless) amounts of BPA can leach out from polycarbonate baby bottles.

- Trace amounts of BPA metabolites have been detected in urine.

- Grant-awarding agencies and scientific journals tend to like sensationalistic results more than actual science.

- The bewildered public has been sold on the notion that evil industry alone has sordid motives, while the fear entrepreneurs are simon-pure.

- There is an appalling lack of understanding of risk assessment even among so-called scientists.

According to the Society of Toxicology…

Risk assessment is a process by which scientists evaluate the potential for adverse health or environmental effects from exposure to naturally occurring or synthetic agents. Risk assessment typically includes an estimate of the probability of harm, and a clear description of the various assumptions and uncertainties that go into the risk assessment.

As you can see, there is far more to risk assessment than merely identifying the presence of a particular chemical. Yet, that very sort of observation is all that is needed to inflame much of the public.

For example, a particular BPA metabolite has been identified in the urine of 93% of the subjects tested by CDC and in another study conducted by Canadian health authorities. This sounds impressive until you discover that the amount detected is only 2.6 micrograms per liter, and this represents an amount 1000 times less than the EPA reference dose—the amount of a chemical expected to cause no harm in humans even if they are so exposed every day of their entire life.

Certainly, the sensitivity of analytical instrumentation has improved dramatically over the past 25 years; but, as has been established by the work of Yoshiyuki Watabe and others, the lab technique of some investigators has not kept pace. Given the ubiquitous nature of BPA, it is likely that the very analytical tools utilized in the detection of this chemical were contaminated with BPA, thus compromising—and overstating—the results.

As noted toxicologist Julie Goodman, Ph.D., Diplomate of the American Board of Toxicology puts it:

There is no proposed BPA ban anywhere in the world that is based on the premise that BPA causes harm. Rather, such bans are said to be based on the Precautionary Principle, which demands proof that something is not harmful—essentially demanding the inherent impossibility of proving a negative.

Dr. Goodman is correct, but no one seems to notice that the Principle is being misapplied.

The Precautionary Principle was first introduced in the US as a result of the Wingspread Conference of January, 1998. Anyone familiar with the state of environmental regulation at the time would be surprised to learn, from the official history of the event, that…

The conferees observed that most existing laws and regulations focus on cleaning up and controlling environmental damage rather than preventing it. The group concluded that these policies do not sufficiently protect people and the natural world.

Had the conference occurred in 1968, the observation would have been accurate, but to proclaim this in 1998—more than 27 years after the founding of EPA—is positively ludicrous.

Undaunted, the conferees stated…

Therefore, it is necessary to implement the Precautionary Principle: When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.

In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof.

The process of applying the Precautionary Principle must be open, informed and democratic and must include potentially affected parties. It must also involve an examination of the full range of alternatives, including no action.

Fair enough. BPA has been used for decades with absolutely no ill effect, and any proposed alternative does not have a fraction of the research data behind it. Therefore, according to the Precautionary Principle, those who propose the ban of BPA should bear the burden of proof. Moreover, those proponents must be open in applying this process.

That’ll be the day. For it is quite obvious that the only interest of the fear entrepreneurs is their own enrichment.