December 12, 2005

Cool Environmental Urban Myths—Part One

By Michael D. Shaw

I guess it all starts out with guilt. Then, mix in some limousine liberal sanitized “outreach” to those less fortunate. Of course, this outreach is more about making the outreacher feel good, than helping the outreachee. Presto! We have the enshrinement of our Native American brethren as true stewards of the environment.

And now, even if much of that has been debunked, two names still come to mind: Chief Seattle and Iron Eyes Cody.

Chief Seattle, whose name lives on in the eponymous Pacific Northwest city, and renowned for his oratorical skills, is said to have given an eloquent speech during treaty negotiations with Washington’s territorial governor, Isaac Stevens. This was in 1854, and the first English translations of the address did not appear until 1887.

However, Henry Smith, the man who published it, did not speak Salish, the language in which Seattle rendered the speech. And, the version first published, with its Victorian flourishes, seems to reflect more of amateur poet Smith, than Seattle; to say nothing of its reference to the inevitable disappearance of the Indians—a viewpoint surely more popular with the white man, than the Indians!

But, more license—much more— would be taken with the speech, adopted by the environmental movement as a sort of manifesto in the early 1970’s…

“I have seen a thousand rotting buffaloes on the prairies left by the white man who shot them from a passing train.”

There are a few problems here. We have no record that Seattle ever traveled to the plains; such buffalo kills occurred long after his death in 1866; and the transcontinental railroad connection did not happen until 1869.

What is there to life if a man cannot hear the lovely cry of a whippoorwill?”

Please. Whippoorwills are not indigenous to the Pacific Northwest.

Finally, one thing he COULD have said in this speech is not documented anywhere, and there are numerous documented speeches of Chief Seattle…

“The Earth is our mother.”

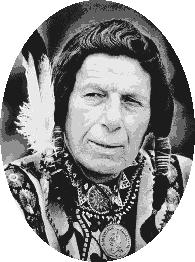

As to Cody, his identification with the Enviro movement occurred in conjunction with a TV public service ad, produced by Keep America Beautiful, entitled “People Start Pollution, People Can Stop It.” The spot first appeared in March, 1971, and featured an Indian (Cody) paddling his canoe down a polluted river, replete with awful smokestacks on the banks, litter all over the place, and trash being strewn at his feet, as he comes ashore. At this, a tear trickles down his cheek.

The smallest problem is that the tear is synthetic, created from glycerin. A bigger issue is that Iron Eyes Cody was no Indian. Born Espera DeCorti in 1904, he was, rather, 100 percent Italian. In 1924, when he started working in the motion picture industry, he changed his name to Cody. He did usually dress in Indian garb, and did his best to maintain the fiction of his origins, even after his birth records were promulgated by a relative.

In Cody’s defense, he pledged his life to Native causes, and married Bertha Parker, an Indian woman. By all accounts, he was generally accepted by the Indian community, even if many of them knew his true ancestry.

There are those in the Indian community who are unhappy with such “innocent” misuses of their ethos. Jack D. Forbes, professor of Native American studies at UC Davis, contends that,

“Native American culture is constantly being exploited and appropriated as illustrations of whatever European theory is in fashion. When will the thefts of our spiritual traditions end?”

A cynic might respond that the theft will end whenever the ACLU decides to litigate against displays of Indian spirituality in the public square.